articles/Photojournalism/darrin-zammit-lupi-moas-page2

Darrin Zammit-Lupi, joined the Migrant Offshore Aid Station - part 2 of 1 2 3

by Darrin Zammit-Lupi Published 01/12/2014

" ...there was no doubt in my mind - these migrants had been sent out there to die."

A rigid-hulled inflatable boat was launched from the Phoenix. Chris Catrambone called out to me from the bridge: "It's your birthday - happy birthday, get in the RHIB and make some great pictures." Three crew members and I climbed in. We were fully dressed in protective gear - disposable coveralls, taped down rubber gloves, masks - no one was taking any chances. Life jackets were quickly loaded and we set off at high speed towards the dinghy. I tried my best to make sure my two camera bodies, carrying 16-35mm and 70-200mm lenses, kept dry as sea spray flew over us. I had decided against using waterproof covers over them as they can sometimes really restrict you and slow down the way you work. The sea wasn't too choppy, so I figured I'd be fine (though I would later thoroughly clean them with wet wipes to be on the safe side). I double-checked that

my head-mounted action video camera was secure and running.

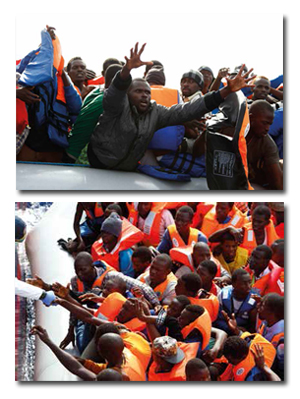

Within minutes, we pulled up alongside the dinghy, packed so tight with sub-Saharan Africans that they could barely sit down. Just one of the 106 immigrants was wearing a life jacket. Their first reaction was one of suspicion - they did not know who we were or what we were doing.

The most important thing to do at this point was to ensure they remained calm and establish contact with someone who spoke some English.

It quickly became clear who the natural leaders among the migrants were. We explained that we were there to help, and that we had already rescued hundreds of their compatriots.

After establishing that there were no women and children on board, nor any particularly ill and injured men, life jackets started to be tossed to them.

This is always a hazardous moment - they began scrambling and fighting over them and we had to repeat over and over again that there were enough life jackets for everyone.

In between taking pictures, I did my part in pleading with them to keep calm.Before we could start getting the migrants onto the ship, I needed to get back on board myself.

After further communication with Rome's Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre, which had earlier assumed coordination of the rescue, it was decided that the safest way to get the migrants onto the Phoenix was to gently nudge the dinghy up against the hull of the ship and to pull them up one by one. Predictably, they all wanted to climb aboard at once.

The biggest danger remained capsizing, even though a rubber dinghy is actually a lot more stable than many people imagine. One man half fell into the water as he tried to scramble on board before it was his turn, and it was only thanks to the fast reaction of a crew member who grabbed his flailing hand that he did not go all the way in or get caught between the ship and the dinghy, with potentially disastrous results.

My heart was pounding as I watched the scene through my viewfinder. They were portraits of utter desperation. Anyone who thinks these people risk their lives by undertaking this deadly journey on a whim really doesn't understand the situation.

The migrants were frisked by the ship's security officers and directed towards the stern, where they sat beneath the helipad. This is where the Phoenix's two remote-piloted Schiebel aircraft, which can monitor the sea from the sky and provide real-time intelligence to MOAS and rescue coordination centres in Malta and Italy, are normally launched.

Please Note:

There is more than one page for this Article.

You are currently on page 2

- Darrin Zammit-Lupi, joined the Migrant Offshore Aid Station page 1

- Darrin Zammit-Lupi, joined the Migrant Offshore Aid Station page 2

- Darrin Zammit-Lupi, joined the Migrant Offshore Aid Station page 3

1st Published 01/12/2014

last update 11/11/2019 11:46:30

More Photojournalism Articles

There are 0 days to get ready for The Society of Photographers Convention and Trade Show at The Novotel London West, Hammersmith ...

which starts on Wednesday 14th January 2026